Kala-Koreysh – fortress of the Quraysh – is a site of significant importance for understanding the spread of Islam in the northern Caucasus. It stands on a small, rocky hilltop, surrounded by two rivers and beyond that, by higher hills and forests – it is an ideal defensive location but difficult to reach even in the present day. The mosque at Kala-Koreysh may have been established by members of the Quraysh clan in the 7th century. It was an important town of the Kaitag feudal state, and one in which a number of its Utsmi (rulers) were buried. The oldest tombstones at the mosque are believed to date from the 12th-13th centuries and the youngest from the 19th century. There are a number of puzzles that have yet to be resolved about the burial practices of the medieval inhabitants of Kala-Koreysh, such as the fact that the earliest were buried in sarcophagi above ground, a practice not permitted in Islam. Both the doors of the mosque and one of these sarcophagi are decorated with zoomorphic motifs, the origin of which is not entirely understood by experts. The data gathered by Factum and Peri, which can be viewed on screen in a variety of formats, may help in unravelling the complex history of this magical site.

The village is almost completely abandoned now and the houses on the hills collapsing. The last villagers were forcefully moved to Chechnya in the 1940s, after the resettlement of a majority of the Chechen population to Central Asia. Their children and grandchildren eventually returned to Dagestan, but because of the remote location and the lack of running water and electricity, they were never able to return to Kala-Koreysh. There is currently only one inhabitant: Bagomed, the guardian of the mosque, who receives the numerous pilgrims that come from all over the northern Caucasus to visit the site in summer months.

Recording Kala-Koreysh

The team lived in the village of Kubachi, an important village of silversmiths in the green, lushly vegetated mountains of southern Dagestan, thirty minutes by car from Kala-Koreysh. In the first two working days at the mosque, the graveyards, mosque, and mausoleum were mapped in preparation for the scanning, and the tombstones and the 12th-14th century sarcophagi located on the grounds. In total, forty-four stones were counted: some complete, others broken – it may be possible to digitally reconstruct a number of these. A number of ‘stumps’, not included in our survey, were also found.

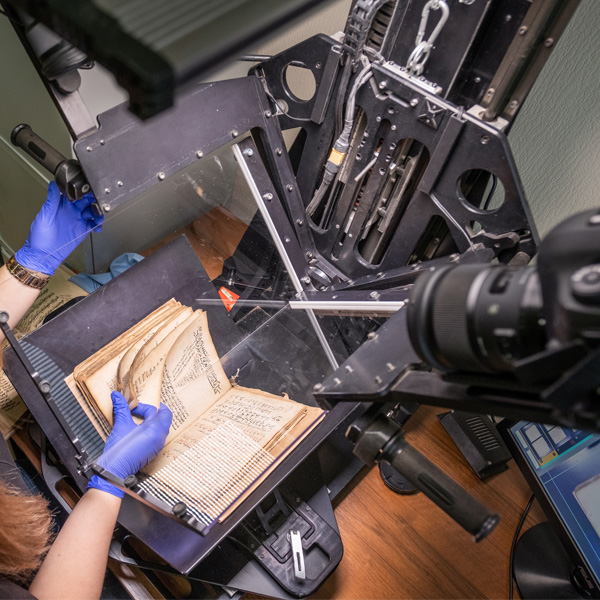

The tombstones and the sarcophagus were recorded using close-range photogrammetry. This is a method whereby multiple overlapping images are taken of the surface of an object, making sure that lighting remains as constant as possible over the surface of the object. The images are subsequently processed using specialized software (in this case RealityCapture was used in post-processing) that maps common pixels, plotting them in 3D space. This method is proving useful because, under the right conditions, it makes it possible to simultaneously record both 3D and colour; the equipment (50megapixel camera, 50mm lens, flashes, and tripod is the basic set) is relatively easy to transport and does not require mains electricity; in comparison to other 3D scanning systems, it is also relatively cheap. At Kala-Koreysh, sliders were used to make the recording more systematic: the camera was placed on the slider and moved horizontally along at set intervals to record one row of images, then lowered by an established distance. The sarcophagus, precariously lying on top of a muddy rock-face above the road, was recorded by hand, and here the photogrammetry equipment proved especially useful – it would have been impossible to record this using more traditional 3D scanning methods. The work was complicated by several days of bad or changeable weather that made the road to the mosque unpassable – but the recording, including a photogrammetric 3D drone-recording of the entire hilltop, was completed in just over two weeks.

The recording of the tombstones at Kala-Koreysh was the first large-scale Factum project realised using only photogrammetry.

All the stones were processed using RealityCapture software. Two of the most important stones were routed in limestone for a Peri Foundation exhibition in 2017 that traced the history and people of Kala-Koreysh. Renders of the 3D data were used by researchers to study texts and symbols on the stones, many of which were in bad condition. Our data makes it possible for a user to view 3D information in black-and-white, something that can highlight information otherwise not clearly visible in 2D photographs.

The Cast Courts at the V&A reopened this November following a long refurbishment. When they first opened in 1873, the purpose of the Cast Courts was to display accurate copies of architectural and sculptural masterpieces from around the world. Over the course of the 20th century the casts also acquired significant conservation value when a number of the original objects were lost or damaged. However, cast making itself has long been considered a destructive technique and in the 21st century new non-contact technologies are finding their way into the Cast Courts.

Today, the Cast Courts also include a facsimile of the tombstone of Kala-Koreysh, realised by Factum Foundation.

Photo © courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum

The mosque doors: from digitisation to facsimile

Render of the doors exterior (left) and interior (right) © Factum Foundation

The four doors of the Kala-Koreysh mosque (10th-12th century) constitute one of the most important examples of Dagestani medieval art. They were at the mosque until at least the 1930s but were removed to the Museum of History and Archaeology in Makhachkala sometime after that. The two pairs, one for the male entrance, the other for the female entrance to the mosque, are made of heavy oak with complex zoomorphic and plant motifs carved in deep relief. Their provenance is uncertain: legend has it that they were once the doors of a Christian church in Kubachi and that the lions and eagles on the fronts had their heads hacked off once Islam had become established in the region.

The scanning took place in one of the museum storeroom with very limited space, the doors photographed on the floor. Several methods were attempted before deciding upon a rig system in which the camera was held on a rail supported by two tripods and photographs taken every 4 cm to achieve nearly 90% overlap on every photograph.

The images were processed using RealityCapture photogrammetry software. One pair of doors was routed (digitally carved) into oak panels. The sides were finished by hand, the oak was coloured, and the panels mounted onto a pair of wooden supports to prevent the wood from buckling. Finally, the knockers were 3D printed and the mould taken from this print cast in iron and glued onto the facsimile. Although the facsimiles of the doors are currently being used for exhibition purposes, it may be possible to return them to the mosque.

Facsimile of the mosque door after milling © Oak Taylor Smith for Factum Foundation

Close up of the carved wooden facsimile © Oak Taylor Smith for Factum Foundation

Close up of the carved wooden facsimile © Oak Taylor Smith for Factum Foundation

Old Kubachi

Kubachi is a prominent settlement in Dagestan, known throughout Russia for its silversmiths and implausible architecture. However, the old village has been almost completely abandoned; there is no running water and the streets are treacherous, making it difficult to comfortably carry water from the well. Because of the slow withdrawal of the population, the buildings in the old Kubachi, including the old mosques are collapsing.

Apart from the loss of architectural and artistic richness, the disappearance of old Kubachi may also result in the loss of a vast number of entirely unrecorded carved stones of historical and cultural significance. In the past, villagers reused the old carved stones in the walls of new houses, but now, as old Kubachi falls apart, the permanence of the stones is no longer ensured.

Two carved stones at the old mosque were recorded using photogrammetry and a number of others photographed as an example of the crucial work that needs to be carried out in the near future.