From Nimrud to Bloomsbury

Lamassu are Assyrian protective deities whose hybrid bodies are part human, part bull or lion, and part bird. Mentioned in the Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh, they were often incorporated into monumental entrance architecture, and the two lamassu now in the British Museum originally flanked the doorway to the throne room of Ashurnasirpal II, king of Assyria from 883 to 859 BCE, in the northwest palace of his capital city at Nimrud.

Nimrud and the nearby city of Nineveh, which are both located a few kilometres away from modern Mosul, were excavated in the 1840s and 1850s, and the main finds were removed from the region. The lead excavators were Austen Henry Layard, a young British archaeologist and imperial agent, and Hormuzd Rassam, the first acknowledged Assyriologist from the Ottoman Empire. Layard’s initial financing came from Stratford Canning, the British ambassador to Constantinople, but following the discovery of the spectacular lamassu statues and widespread interest in the finds from the general public, the British Museum began to provide funding for the excavations, and for shipping the finds from Basra to London.

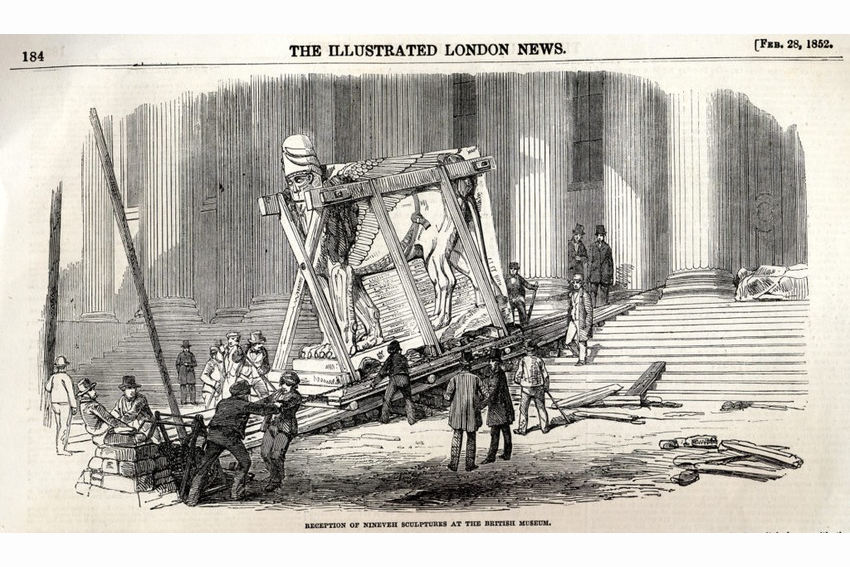

An illustrated London newspaper from 1852 shows the arrival of the lamassu at the British Museum, where they caused a sensation: in 1853 The Times reported that ‘The researches of Mr Layard have not only rendered Assyria an object of interest to professed antiquaries, but have actually brought it into fashion… Everyone knows the form of an Assyrian monarch’s umbrella, and the fashion of the Royal crown of Nineveh is as familiar as the pattern of the last new Parisian bonnet.’

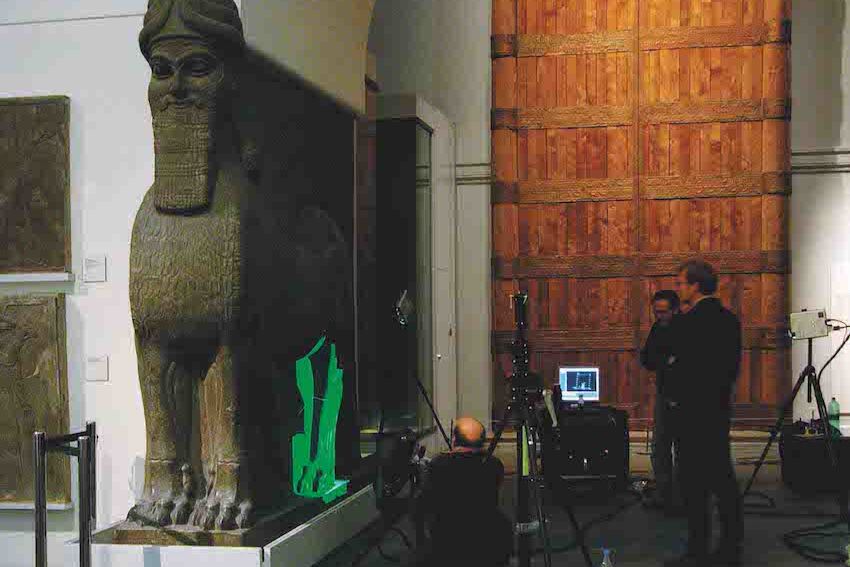

In 2004, Factum Arte (before the creation of Factum Foundation in 2009) recorded the original statues at the British Museum using a high-resolution NUB3D scanner. Multiple tests were also carried out to assess the precise colour and texture of the lamassu, allowing for the creation of a suitable material – stucco marble – for the making of the facsimiles.

Scanning the lamassu at the British Museum © Factum Arte

Alongside the lamassu, other reliefs from the palaces at Nimrud and Nineveh were also scanned, not only in the British Museum but also in the Pergamon Museum, the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, the Sackler Museum at Harvard University and the Princeton University Art Museum. These include numerous large-scale low-relief narrative scenes and even one panel designed to resemble a carpet or wall hanging. Further fragments in Iraq still remain to be recorded.

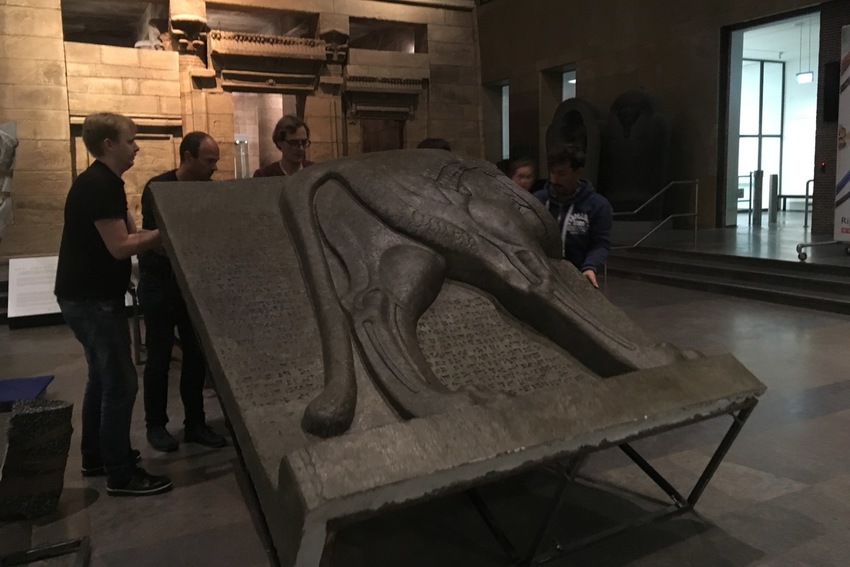

The scanned data was then processed and prepared for one of the largest high-resolution routing projects ever undertaken for conservation purposes. The data was routed in sections in high-density polyurethane, and after the different parts had been put together to verify the overall fit, silicone moulds were made of each section and the routed sculptures were cast in stucco marble. A final coat of wax completed the imitation of the original gypsum surface, bringing the colossal winged lions back to life in Factum Arte’s Madrid studios.

Prototype of the winged lions

An interior metal structure supports each section

The facsimiles were assembled at the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden for their exhibition 'Nineveh'

Finalising the details

In early 2014, Factum Foundation and the British Museum donated plaster casts of the relief panels now in the British Museum for exhibition at the Ashurbanipal Library, an ambitious new centre located next to the archaeology department of Mosul University which aims to provide a hub for the study of Iraqi history and monuments. The building is named for Ashurbanipal, a later ruler of Assyria (668-c. 630 BCE), in whose capital at Nineveh (80km upriver from Nimrud) over 30,000 cuneiform tablets and fragments were found by Layard and Rassam, and was intended to contain a museum, research centre, and several rooms for national and international symposia. Since 2002, the British Museum’s Ashurbanipal Library Project has worked closely with this institution, spearheading a major effort to assemble, digitise, and translate the known texts from Nineveh, on subjects ranging from divination to administration to literature. Tragically, however, the Ashurbanipal Library suffered heavily during the occupation of Mosul by Islamic State – a disaster which resulted in the devastation of much of the city as well as the site of Nimrud itself, and as of late 2019 in the displacement of over 300,000 residents. It is hoped that work on this vital centre for Iraqi heritage will be part of the rebuilding of the city in the years ahead.

In 2017, permission was given to make a new copy of the two lamassu, this time for the exhibition ‘Nineveh’ at the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden. The facsimiles were made on the understanding that after the exhibition they would be transported to Mosul as a gift to the people of Iraq, and in September 2019 the Spanish Ministry of Defense generously flew the vast statues to Baghdad. They were unveiled at the University of Mosul in October 2019, where they were installed at the entrance to the university library.

This is a project which would not have been possible without the collaboration and financial and practical support of the British Museum in London, Mosul University, the Rijksmuseum Van Oudheden, the Spanish Ministry of Defense and the Iraqi Government. All parties hope that the installation of the facsimiles will be seen as a gesture of solidarity and a sign of hope for the role that technology and cultural heritage can play in the reconstruction of the Republic of Iraq.

In addition to sending the two lamassu to Mosul, the Factum/Frontline initiative will also train local archaeologists in photogrammetry for heritage recording, providing them with the skills to record their own material culture. Luke Tchalenko has been trained as the first photojournalist able to offer such teaching, while remote support will be provided by Factum’s team in Madrid.